A few years

ago Brigham Young University sponsored an academic conference to explore and

present new research on the Latter-day Saints’ concept of the apostasy of the

primitive, or meridian, Church of Jesus Christ. This volume was the result: Standing Apart: Mormon Historical

Consciousness and the Concept of Apostasy. I have not read this book

(except for a version of the epilogue) and therefore cannot personally speak to

it. I have read a

review posted by someone at the Neal A. Maxwell Institute at BYU, which

included this sentence: “The authors aren’t shy about respectfully challenging

claims made by LDS leaders as well as prominent LDS scholars.”

If this

sentence accurately reflects the book’s content, one wonders why BYU would

sponsor such a conference that challenged the teachings of its leaders. Be that

as it may, I personally have no problem when scholars do legitimate, rigorous

and sound research and present/interpret/publish their findings, as long as

those findings are in harmony with revelation and how such revelation is

interpreted by those who hold the keys. For myself, I have always placed the

word of God over the word of scholars that tends to change a lot. If scholars’

findings tell us that we have misunderstood to some extent a long period of time

in the past, that is just fine. If we learn that much of enlightening value,

more than we knew before, went on during the middle ages, or, that various

persons over the centuries received divine knowledge or an occasional gift of

the spirit via the light of Christ—that’s fine, no problem. Such knowledge

might even have some use somewhere somehow. (I hope these scholars don’t think

they now know all about the past.)

However, if

these scholars’ purpose is to reinterpret/weaken the historical narrative of

the apostasy and restoration of the Church of Jesus Christ to the point of

almost eliminating it (and for some of them it seems it is) then we should take

instant strenuous issue and cry foul. Anything that denies the loss of the

priesthood, keys, the gift of the Holy Ghost, and temple ordinances after the

death of the apostles is false. Likewise, anything that denies that true and

pure gospel doctrine and ordinances became corrupted and sullied with the

passage of the centuries, is also false and insidious.

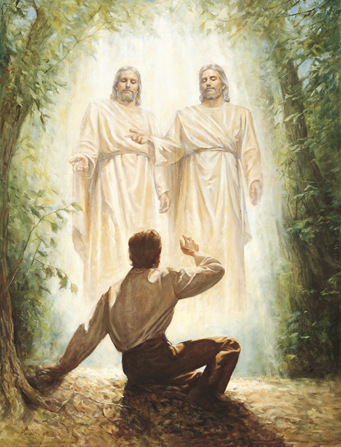

One popular

modern scholar has gone to some lengths to insist that the Church established

by Jesus figuratively walked off and hid behind a tree in the wilderness for

many centuries and was really hanging around all along to come back with Joseph

Smith’s assistance. Also that the LDS Church’s only real purpose, that

separates it from others, is to act as the custodian/guardian of the temple

ordinances. To any who have been beguiled by such falsehoods, I recommend

reading a few works by a much more dependable and knowledgeable scholar: The World and the Prophets, Apostles and Bishops in Early Christianity,

and When the Lights Went Out: Three Studies on

the Ancient Apostasy; such should help, along with the below, to

correct such misleading interpretations and errant notions.

I, for one,

hope that when scholars pit their academic learning against the revelations and

teachings of modern prophets and apostles, we can be wise enough to choose

correctly which to believe and where to place our faith and trust. If not, it

is time to call all of the missionaries home; time to encourage people to

attend other Churches; to cast our eyes and ears upon Popes and televangelists;

to accept the baptism of any Christian religion; to shut the mouths of apostles

who bear witness of Jesus the Christ, His restored gospel, the divine calling

of Joseph Smith, and so on. Perhaps Joseph should have told Peter, James, and

John, and John the Baptist that the authority they were restoring was not

really necessary. Perhaps when Moses and Elijah and others showed up in the

Kirtland Temple to bestow their keys, Joseph and Oliver should have told them

it was unnecessary; they could go back to heaven. Joseph could get whatever

doctrine he needed from the Catholics and Protestants.

Over the last several years, I have

heard too many talks given by living apostles regarding the cold hard fact that

an apostasy occurred around AD 100; that it lasted until 1820, and that Joseph

Smith was the instrument that Jesus used to restore true knowledge, priesthood,

keys, ordinances, and powers. Further, that the apostasy is still going strong

outside where these keys operate. There is NO other acceptable narrative or

view to take regarding these fundamentals and anyone teaching such is

misleading others. I sincerely hope the aforementioned new book largely clarifies

instead of misleading. If someone wants to know how bad/deep the apostasy

eventually got, simply look around outside The Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-day Saints and observe how the world is doing in religious matters. And

read the below, as quoted in Determining Doctrine:

The First Presidency (Heber J. Grant, J. Reuben Clark Jr.,

David O. McKay, 1944):

Courses on

"comparative religion" have no place otherwise than in the

Post-Graduate School to be established at the Brigham Young University and

there only for the purpose of developing and demonstrating the truth of the

Restored Gospel and the falsity of the other religions of the world, and

thereby build the faith and knowledge of post-graduate scholars. The subject is

one for careful, prayerful study by the mature mind, not for the framing of the

thought and belief of the youthful mind. (James R. Clark, comp., Messages of

the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6

vols. [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965-75], 6:210.)

J.

Reuben Clark:

In a

commandment given to Leman Copley (March, 1831), as he went into missionary

work among the Shakers, the Lord gave this significant commandment, which has

in it a message for all amongst us who teach sectarianism: "And my servant

Leman shall be ordained unto this work, that he may reason with them, not

according to that which he has received of them, but according to that which

shall be taught him by you my servants; and by so doing I will bless him,

otherwise he shall not prosper." (D&C 49:4.) ("When Are the Writings or Sermons of

Church Leaders Entitled to the Claim of Scripture?" second part of an

address delivered July 7, 1954 at Brigham Young University; cited in David H.

Yarn, ed., J. Reuben Clark: Selected Papers,

vol. 3 [Provo, UT: BYU Press, 1984], 97.)

J.

Reuben Clark:

Read your books. There is a startling parallel between the

course that is coming in to us today and the course that was in the early

Church, so startling that one becomes fearful. We have these little groups

going off on their own doing their own interpreting of the scriptures, more or

less laying down their own principles. They are small now, of no particular

consequence, but that is the way it began in the early Christian Church, and these

little snowballs grew and grew and grew until they became great.

"Scholasticism" took its root among those early

peoples. There were a number of "schoolmen," they were called who

undertook to define the doctrines of the early Church, then developing into the

great Catholic Church—Bede, Alcuin, Damiani, Scotus, and others, Thomas

Aquinas—they began the development, these individuals, of great heresies that

took hold of the imaginations of the people and finally were adopted by the

Church.

Now, of

course, the Church in those days was not organized as we are. The bishops were

independent, one from the other. They had no real, there was no real central

control. The pope exercised some, but it was very ineffective and inefficient.

Some popes ruled some of these heresies wrong as heresies, then later other

popes came along and ruled them as truths. (Conference Report, April 1952, 81.)

M. Russell Ballard:

History tells us, for example, of a

great council held in A.D. 325 in Nicaea .

By this time Christianity had emerged from the dank dungeons of Rome to become

the state religion of the Roman Empire, but the church still had

problems—chiefly the inability of Christians to agree among themselves on basic

points of doctrine. To resolve differences, Emperor Constantine called together

a group of Christian bishops to establish once and for all the official

doctrines of the church.

Consensus

did not come easily. Opinions on such basic subjects as the nature of God were

diverse and deeply felt, and debate was spirited. Decisions were not made by

inspiration or revelation but by majority vote, and some disagreeing factions

split off and formed new churches. Similar doctrinal councils were held later

in A.D. 451, 787, and 1545 with similarly divisive results. (Conference Report,

October 1994, 85.)

Dallin H. Oaks:

We maintain

that the concepts identified by such nonscriptural terms as “the

incomprehensible mystery of God” and “the mystery of the Holy Trinity” are

attributable to the ideas of Greek philosophy. These philosophical concepts

transformed Christianity in the first few centuries following the deaths of the

Apostles. For example, philosophers then maintained that physical matter was

evil and that God was a spirit without feelings or passions. Persons of this

persuasion, including learned men who became influential converts to

Christianity, had a hard time accepting the simple teachings of early

Christianity: an Only Begotten Son who said he was in the express image of his

Father in Heaven and who taught his followers to be one as he and his Father

were one, and a Messiah who died on a cross and later appeared to his followers

as a resurrected being with flesh and bones.

The collision between the

speculative world of Greek philosophy and the simple, literal faith and

practice of the earliest Christians produced sharp contentions that threatened

to widen political divisions in the fragmenting Roman

empire . This led Emperor Constantine to convene the first

churchwide council in A.D. 325. The action of this council of Nicaea remains the most important single

event after the death of the Apostles in formulating the modern Christian

concept of deity. The Nicene Creed erased the idea of the separate being of

Father and Son by defining God the Son as being of “one substance with the

Father.”

Other councils followed, and from

their decisions and the writings of churchmen and philosophers there came a

synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine in which the orthodox

Christians of that day lost the fulness of truth about the nature of God and

the Godhead. The consequences persist in the various creeds of Christianity,

which declare a Godhead of only one being and which describe that single being

or God as “incomprehensible” and “without body, parts, or passions.” One of the

distinguishing features of the doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-day Saints is its rejection of all of these postbiblical creeds (see

Stephen E. Robinson, Are Mormons

Christians? [Salt Lake City : Bookcraft,

1991]; Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed.

Daniel H. Ludlow, 5 vols. [New York :

Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992], 1:56 -58,

1:393-404, 2:548-53).

In the process of what we call the

Apostasy, the tangible, personal God described in the Old and New Testaments was

replaced by the abstract, incomprehensible deity defined by compromise with the

speculative principles of Greek philosophy. The received language of the Bible

remained, but the so-called hidden meanings of scriptural words were now

explained in the vocabulary of a philosophy alien to their origins. In the

language of that philosophy, God the Father ceased to be a Father in any but an

allegorical sense. He ceased to exist as a comprehensible and compassionate

being. And the separate identity of his Only Begotten Son was swallowed up in a

philosophical abstraction that attempted to define a common substance and an

incomprehensible relationship.

These descriptions of a religious

philosophy are surely undiplomatic, but I hasten to add that Latter-day Saints

do not apply such criticism to the men and women who profess these beliefs. We

believe that most religious leaders and followers are sincere believers who

love God and understand and serve him to the best of their abilities. We are

indebted to the men and women who kept the light of faith and learning alive

through the centuries to the present day. We have only to contrast the lesser

light that exists among peoples unfamiliar with the names of God and Jesus

Christ to realize the great contribution made by Christian teachers through the

ages. We honor them as servants of God. (Conference Report, April 1995,

112-13.)

Stephen

E. Robinson:

Suppose for a moment that the

Latter-day Saints were to take seriously the demand that they conform in every

particular to "Christian" doctrine, and that they then made the

attempt to do so. Having complied with such a demand, would the Latter-day

Saints find themselves in total agreement with Protestants or with Catholics?

Would they believe in apostolic succession or in the priesthood of all

believers? Would they recognize an archbishop, a patriarch, a pope, a monarch,

or no one at all as the head of Christ's church on earth? Would they be saved

by grace alone, or would they find the sacraments of the church necessary for salvation?

Would they believe in free will or in predestination? Would they practice water

baptism? If so, would it be by immersion, sprinkling, or some other method?

Would they believe in a substitutionary, representative, or exemplary

atonement? Would they or would they not believe in "original sin"?

And on and on.

It is unreasonable for other

Christians to demand that Latter-day Saints conform to a single standard of

"Christian" doctrine when they do not agree among themselves upon

exactly what that standard is. To do so is to establish a double standard;

doctrinal diversity is tolerated in some churches, but not in others. The

often-heard claim that all true Christians share a common core of necessary

Christian doctrine rests on the dubious proposition that all present

differences between Christian denominations are over purely secondary or even

trivial matters—matters not central to Christian faith. This view is very

difficult to defend in the light of Christian history, and might be easier to

accept if Protestants and Catholics—or Protestants and Protestants, for that

matter—had not once burned each other at the stake as non-Christian heretics

over these same "trivial" differences. (Stephen E. Robinson, Are

Mormons Christians? [Salt Lake

City : Bookcraft, 1991], 58.)

Joseph Fielding McConkie:

We are

obligated to bring the best of our scholarship to bear on the study of the Book

of Mormon and all other scriptural records. We do not have the right to do

less, but we cannot substitute the evidences of men for the witnesses of the

Spirit. Scholarly decoys are the danger here. Some seem to be more interested

in proving the Book of Mormon true than in discovering what it actually

teaches. The irony is that the only meaningful evidence that the book is true

is its doctrines. Faith is available to all on equal grounds, as are answers to

prayers—scholarly understanding is not. When those who do not have the

necessary academic skills are induced to build the house of their understanding

of blocks supplied by scholars, they become beholden to the scholars. They find

themselves out of context. The scholar then stands between them and God. That

is precisely what happened in the Great Apostasy and brought the meridian

dispensation to an end. Scholars replaced prophets, and the gospel was declared

a mystery that could be understood only by those who had been schooled and

trained for the ministry. Thus the trained minister was placed between the

believer and God. (Here We Stand [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co.,

1995], 120-21.)

Hugh Nibley:

When the

covenants were broken and the ordinances changed, and the churches taught for

doctrines the commandments of men, the old gospel was simply no longer there.

Today church historians, Protestant and Catholic alike, agree that this was so,

and they easily reconcile themselves to the situation by insisting that what

took the place of the old church was really something much better, something

far more fit for survival in a wicked world, much more available to the grasp

and amenable to the taste of the average man. The early church, they explain,

was something hopelessly impractical and of extremely limited popular appeal;

therefore, it had to go; it was merely a tiny acorn from which a mighty oak was

to grow, etc. Well, what interests us here is not their explanation and

justification of what happened, but the admission that it did happen. The

primitive church was changed, and thereby the primitive church was lost. And to

this we add the thesis that such loss was an irreversible process. Reformation

could no more bring it back than it could bring back Old English,

eighteenth-century monarchy, or the thinking of the Scipionic Circle . (The World and the

Prophets, 3rd ed. [Salt Lake City and Provo, Utah: Deseret Book and FARMS,

1987], 119-20.)

Hugh

Nibley:

If we have said a great deal about

the falling away and the loss of the true gospel to mankind in ancient times,

let us make it clear here and now that such a teaching is not a part of

the gospel at all; it is not found in the Articles of Faith; it has no bearing

at all upon the plan of life and salvation; Joseph Smith almost never referred

to it. We only mention the great apostasy because it is an historical point on

which we are constantly being challenged: "How can you say," we are

asked every day, "that the gospel of Jesus Christ has been restored to the

earth if the Christian church has never ceased to be here?"

One answer to that question is found in the activities of

the reformers. Let us make it clear that the attempt to reform the Christian

church to its lost state of pristine purity did not begin with Luther. In every

century since the Apostles men have made determined attempts to reform the

church, and they have always run into the same problem that Luther did, namely

the question: Who has the right to inaugurate reform? We know who can amend the

Constitution, as we know who established it. But with the church it is an

entirely different thing. It was established by Jesus Christ personally. If any

amendments, changes, or reforms are in order, they should be his doing, but how

can that be unless he speaks to men by revelation? (The World and the

Prophets, 3rd ed. [Salt Lake City and Provo, Utah: Deseret Book and FARMS,

1987], 122.)

Bruce R. McConkie:

There is no salvation

outside The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salvation is available

in and through this great latter-day kingdom and it only. “whosoever belongeth

to my church [and as we have seen ‘my church’ by express, revealed definition

is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints] need not fear, for such

shall inherit the kingdom of heaven. . . . Behold, this is my

doctrine—whosoever repenteth and cometh unto me, the same is my church.

Whosoever declareth more or less than this, the same is not of me, but is against

me; therefore he is not of my church. And now, behold, whosoever is of my

church, and endureth of my church to the end, him will I establish upon my

rock, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against them.” (D&C 10:55,

67-69.). . .

“And

wo unto them who are cut off from my church [remember the revealed definition

of ‘my church’] for the same are overcome of the world.” (D&C 50:8.)

As

surely as the Lord lives, those who are cut off from his kingdom, unless they

repent and return to him with all their hearts, shall receive sorrow rather

than salvation, anguish in place of joy, and spiritual degeneracy instead of

eternal life. (Bruce R. McConkie, Pamphlet, Cultism

as Practiced by the So-Called Church of the Firstborn of the Fullness of Times,

Salt Lake City, 1961, 33-34.)

No comments:

Post a Comment